Einstein’s theory of relativity presented time as existing in a four-dimensional structure together with space.[1] Time, now freed from the idea of a line that progressively connects point a to point b, presents an opportunity to re-think the terms we use to characterize its passing.

Now, imagine this applied art history. Traditionally, the field has dealt with artistic production chiefly in categories some of which refer to the culture or place they originated in, and others to the respective time period. Time periods can easily be seen as following one after the other. However, if we consider time as a three-dimensional movement, much like a cubist painting, any two art historical periods can technically meet at any given point in time. As a result, connections between one period and another, and the cultures that

Traditionally, the field has organized artistic production chiefly in categories some of which refer to the culture or place they originated in, and others to the respective time period. Time periods in such cases can be seen as following one after the other. However, as many historians have pointed out, the periodization of art often presents problems. Considering the many understandings of the term “gothic” would be enough to illustrate this point. If time is considered as a four-dimensional concept, much like a cubist painting, any two “periods” can technically meet at any given point and be seen from any one perspective. What could result is multiple connections between different artistic practices that occurred at different moments. The cultures that had bred them could also be seen through a different lense and become connected in new ways. This, in turn, can lead to an understanding of art history where periods and cultures are not so much described in progressional and comparative terms but in terms of similarities.

In the past few years, scholarship has taken an interest in the matter of connections between time periods that do not necessarily follow each other linearly. The discussions they incite are fascinating. For anyone interested to read more I include a list (alphabetical) and a short review of publications below. Each of these writings has greatly influenced my own cross-temporal studies and research methods. If you have already acquainted yourself with the grappling issue of addressing time in art history, please feel free to comment below.

* Betancourt, Roland and Maria Taroutina eds., Byzantium/Modernism: The Byzantine as Method in Modernity, in Visualizing the Middle Ages vol. 12, edited by Eva Frojmovic. Leiden/Boston: 2015.

This particular edition does not overtly address approaching art historical practice cross-temporally, but in the interdisciplinary essays that form its whole, Byzantine practices can be seen as influencing the modern and contemporary and less as an isolated period of the past (as it often tends to be understood). It is a fascinating read that brings to the foreground aspects of modern practices that are reflected in Byzantium, as well as blocks created by the Modern method of reading architecture in approaching Byzantine works.

* Crow, Thomas, No Idols: The Missing Theology of Art. Sydney, AT: Power Publications, 2017.

This book is cross-temporal but in a different sense than the ones that follow in this list. Thomas Crow here presents the (rather taboo) issue of discourse on Contemporary art lacking reference to the divine. The element of the divine was a guiding force not only of art but of people themselves up until the Renaissance. In this exciting new book, Crow suggests that “a religious art, as opposed to ‘a simulacrum of one’, is conceivable for our own time.”[1]

* Hahn, Cynthia et al., Objects of Devotion and Desire: Medieval Relic to Contemporary Art, exhibition catalog, January 27 – April 30, 2011, Hunter College, New York.

This catalog is a particular favorite as it is the result of the work of professor and curator Cynthia Hahn, and the projects of her students at Hunter College. The exhibition it accompanied spoke directly to the subject of crossing traditional understandings of temporality and created an immediate connection between the Byzantine and the Contemporary art worlds. Through this project, Hahn opened a direct dialogue on the use of time by art history and curatorship. The catalog additionally points to similarities between contemporary art practices with those of the past that may otherwise be seen as outdated. [FIY the link above leads to a digital copy of the catalog]

* Nagel, Alexander and Christopher Wood, Anachronic Renaissance, Zone Books, New York, 2010.

Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood open the issue of anachronicity in Renaissance art by examining notions of repetition, originality, and authenticity.

* Nagel, Alexander, Medieval Modern: Art out of Time, Thames & Hudson, New York, 2012.

In this book, Nagel looks at cross-temporal connections between pre-modern and modern historical periods truly breaking the textbook approach to looking at art as “progressing” through time. What is more, the book is organized in a way that eases the reader into the subject and grasps their attention to the point of not wanting to set it aside.

* Powell, Amy, Depositions: Scenes from the Late Medieval Church and the Modern Museum. New York: Zone Books, 2012.

Amy Powell approaches medieval (European) images of the deposition of Christ to discuss a more general idea of images that have or await their own deposition. In so doing she takes on a new view of European iconoclastic uprisings and what they mean for art later on. All chapters are accompanied by sets of images of medieval and modern works which often present formal similarities. Overall, this book presents a fresh and unique re-looking at medieval art and European religious history, as well as of works we are closer to time-wise.

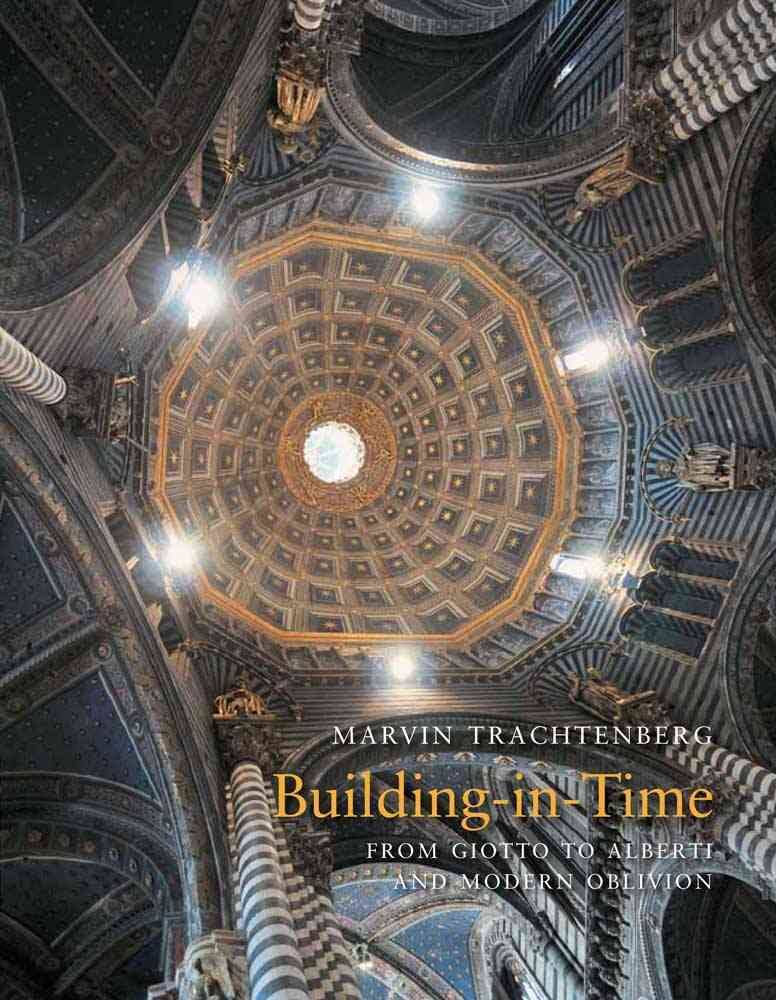

* Trachtenberg, Marvin, Building-in-time: From Giotto to Alberti and Modern Oblivion, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2010.

Marvin Trachtenberg warites about architecture with a particular focus on the so-called Gothic and the Renaissance periods. He grapples with the problems that arise from the use of the term “Gothic” that has come to characterize not just a style, but also a time period that is often dated flexibly. The matter of time in architectural history is addressed additionally by questioning the true beginning of the Renaissance. Building-in-Time is the original concept Trachtenberg uses to present the buildings as works that evolve over large spans of time and therefore challenges their attribution to any one single period. His propositions have caused a considerable stir, as tends to happen with non-traditional approaches in a very traditional field which is just one extra reason to pore over this work.