About the author:

In light of the quarantine-imposed limitations in art seeing, we will seek to bring you closer to exhibitions now out of reach by way of thoughtful reviews.

Our guest contributor Jennifer Contreras who reviews two major exhibitions in New York that suffered the consequences of coinciding with a global pandemic. Jen is a New York-based art historian and writer who splits her time between the art world and fitness. I had the privilege of meeting and befriending her in graduate school when our entire lives evolved around art, its history, and the mesmerizing interconnectedness between different periods and backgrounds. Below, you will find Jen’s first review of the recent exhibition Vida Americana at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

As the fitness industry in New York, along with the remainder of the country, takes an indefinite “pause,” I have taken the opportunity to devote some long overdue attention to another longtime pursuit of mine: Modern and Contemporary Art History. What follows will be a series of brief articles covering recent exhibitions of note in New York City, which will (hopefully) be on view once museums are allowed to reopen to visitors. It is my hope that anyone reading this will have taken time over the past few weeks to reconnect with something that makes them truly happy, and that we will all have the chance to do and see those things which bring us joy in the near future. As for me, my first order of business will be to grab a great cup of coffee in my favorite city on Earth, and go see some art.

As someone who has both studied and deeply admired Jackson Pollock’s work for nearly two decades, the Whitney Museum of American Art’s recent exhibition entitled Vida Americana feels at once timely and long overdue. The show gathers some 200 works by 60 Mexican and American artists, including painting, sculpture, film, and facsimiles of major in-situ murals, and makes a strong case for the symbiosis of ideas in the American and Mexican Modernist traditions. It is well worth mentioning that Vida Americana is a show comprised mostly of Mexican artists assembled by and displayed in a self-proclaimed museum of American art. This could be viewed as a subtle nod to inclusivity, the broadening of a major museum’s scope, or a bold definition of what it means to be modern, or American. As with most of the Whitney’s programs, Vida Americana is likely a combination of all three, making it deeply enjoyable for the casual museum-goer and art world insider alike.

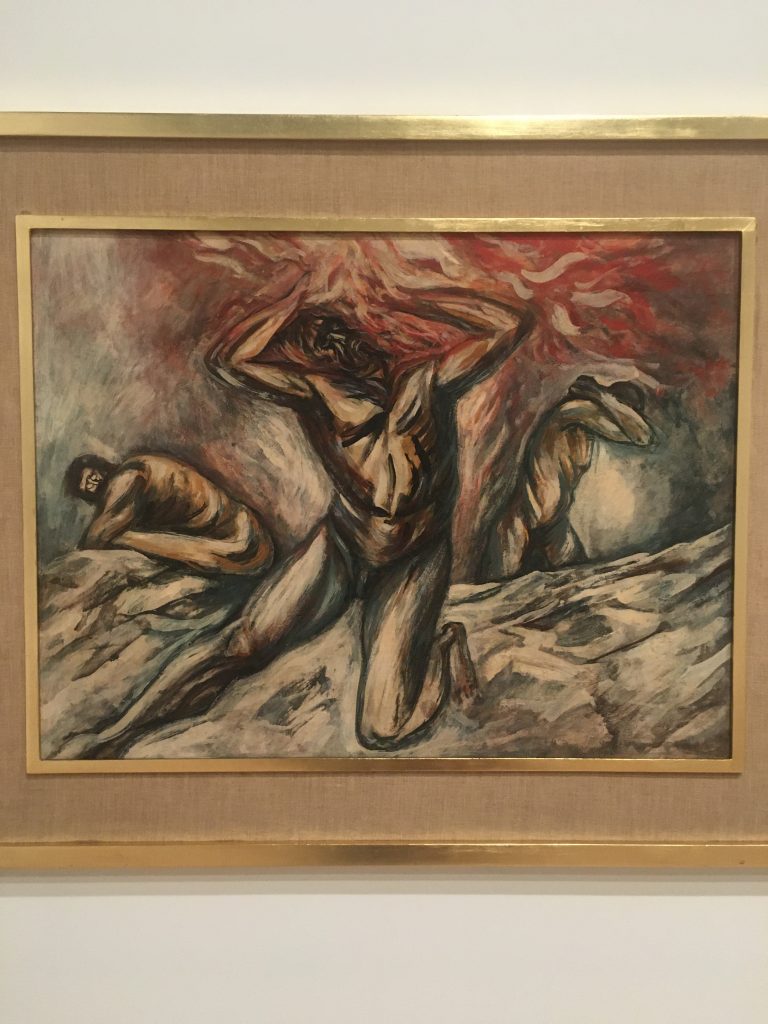

Much of the American portion of the exhibition hinges on Pollock’s early work – you will find no classic “drip” paintings here – and much of the conventional literature on this work attributes the influence of regionalist mentor Thomas Hart Benton as much if not more than Mexican Modernists David Alfaro Siquieros and José Clemente Orozco. The most germane treatments of the artist’s early paintings recognize the seminal influence of Siquieros and Orozco, but do little more than detail Pollock’s familiarity with their well-known murals. Vida Americana allows a rare opportunity to closely examine a great number of these works together, and, along with the intelligent pairings which abound throughout the show, recreate some of the specificity around the compelling and enduring impact the two Mexican modernists had on Pollock’s early work. After all, it is Siquieros who favored the “controlled accident” which would become a fundamental approach to Pollock’s technique, driving both his own artistic practice and an oeuvre that helped define the course of modern art history. The exhibition rightly places excellent works by “Los Tres Grandes” (Siquieros, Orozco, and Diego Rivera) right alongside Pollock’s late 1930s and early 1940s rarely shown, turbulent and troubled works. On the surface, they could hardly differ more sharply from the “classical” large scale drop paintings of 1947-1950 for which Pollock is known and to which he will (radically) turn, although the later work will hinge on the ideas he is working through here. What was particularly satisfying in the show’s arrangement was the reproduction of Orozco’s Prometheus mural from 1930, which Pollock famously made a pilgrimage to Pomona College to see. He kept an image of the work in his studio throughout the 1930s, so it would likely have been on his mind as he completed paintings such as “Untitled (Naked Man with Knife),” c. 1938-40 on view nearby.

Even without knowing their intertwined histories, the feeling of mass, of struggle, monumental scale and “full bodied muscularity” are brought to vivid life by thoughtful and numerous pairings in the Whitney’s show.

While Pollock ultimately – and necessarily – abandons these along with all other influences during the classical drip phase of his work, what remains throughout is what binds Mexican and American Modernism together: a public ambition writ in the language of private, everyday, “everyman” life – romantic notions of immediacy and truth – of art’s ability to change the world. Vida Americana’s impact from the works it represents is just as convincing as the curatorial program behind the exhibition, and the best part of all is that Frida Kahlo, with paintings like Me and My Parrots, (1941) and “Two Women (Salvadora and Herminia),” (1928) inevitably and unsurprisingly, steal the show.