Alexandra Zsigmond is a New York-based artist of Greek and Hungarian heritage, originally from San Francisco. Her paintings, drawings, and prints are grounded in an exploration of semiotic systems and typography. Alexandra is also a curator and designer of exhibitions, books, and newspapers, and was an art director for The New York Times’s Opinion and Sunday Review sections from 2010–17. She is a recipient of the Public Scholars Fellowship from Humanities New York in 2015 and has given talks and workshops on editorial art worldwide.

We reached out to her in 2020 to talk about her overall artistic practice, and learn more about her work on Greek tamata (votives) specifically. Alexandra’s votives offer a contemporary meditation on the ancient tradition, at a time when issues of sickness and health are all the more relevant amid an ongoing worldwide pandemic.

Tamata are small, palm-sized metal sheets embossed with the image of a body part or object to symbolize a physical ailment or emotional concern. They could depict a leg, eyes, or even an infant if the individual is hoping to conceive. These votive offerings are then taken to a church of choice as a form of prayer and hung near the icon of the holy figure to whom the prayer is addressed. They can be seen in churches all across Greece, from the mainland to the islands. The isolated body parts on tamata form an abstracted visual vocabulary; when seen outside of the church context, this vocabulary loses some of its iconographic, narrative meaning. When encountered in a liturgical setting, tamata exude an almost mystical sense.

Alexandra’s fascination with tamata began early in life. Being of Greek descent on her mother’s side, with relatives in Athens and Aegina whom she visited regularly, she was raised in the votive tradition. In addition, she was born with a congenital heart defect and grew up seeing her heart’s activity represented in charts and graphs, which spurred her interest in visualizations of illness and in heart votives specifically. In Fall 2019 she decided to merge these personal and aesthetic concerns into a research-based art residency at A-DASH Project Space in Athens.

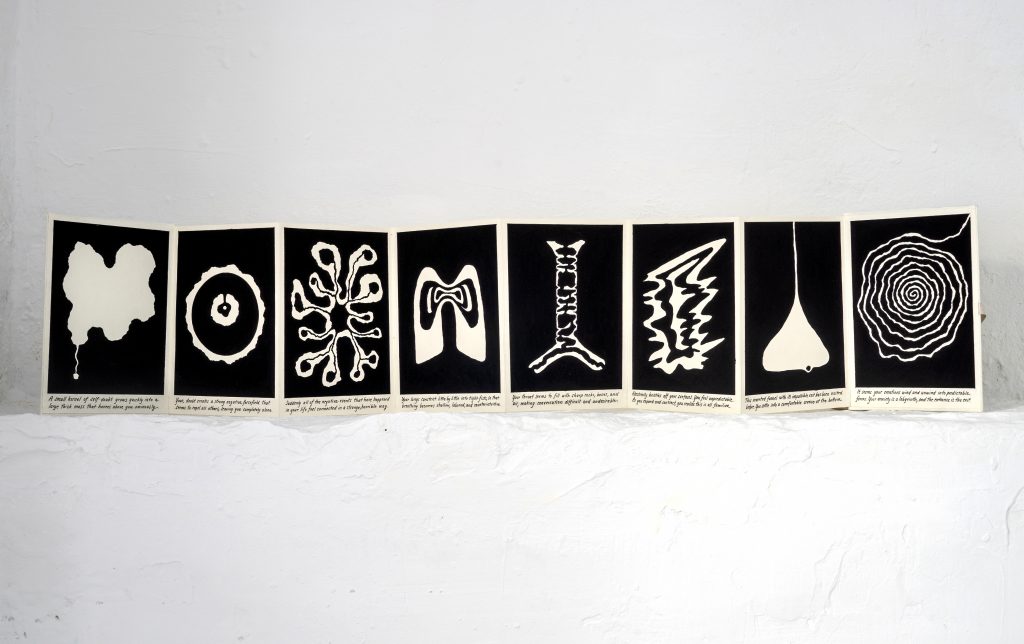

During the residency, Alexandra researched the history of Greek votives and was struck by their reliance on a visual vocabulary rooted in physical objects and body parts. She set out to invent new visual lexicons for tamata, ones that could address the more interior, psychological ailments of anxiety, overthinking, fear, and fatigue. She began this process with a series of drawings and paintings to expand on existing votive iconography (such as the traditional eye tama), and to invent new schematic languages for the experiences of anxiety and overthinking. These lexicons then became the basis for a collection of hand-embossed tamata on copper and tin. Her tamata can be used like the traditional ones—hung in holy spaces as prayers—but they offer protection from more invisible, interior ailments rather than entirely physical ones. She exhibited this series at A-DASH in November 2019, at the end of her residency there. Alexandra is now working on a new series of tamata specifically for Covid-19, as well as for a broader array of viruses and autoimmune diseases.

The process of giving visual form to something which ails you seems deeply meditative and potentially healing in and of itself. It allows the individual to personify their condition, giving them control over how they perceive their own physical and emotional experience. Per a growing number of psychologists, visualizing an ailment or problem gradually creates the confidence that it can be eradicated. It is far easier to battle a (proverbial) enemy that one can actually see. It is thus evident that through this practice of expanding the lexicon of tamata, Alexandra is able to bridge the disciplines of fine art and psychology.

In addition, the process of creating new visual iconographies demonstrates the conceptual, diagrammatic, and systematic nature of Alexandra’s work. Aside from her series of tamata, Alexandra’s overall practice seems to revolve around the documentation of existing visual lexicons in art history and culture, and the invention of new ones.

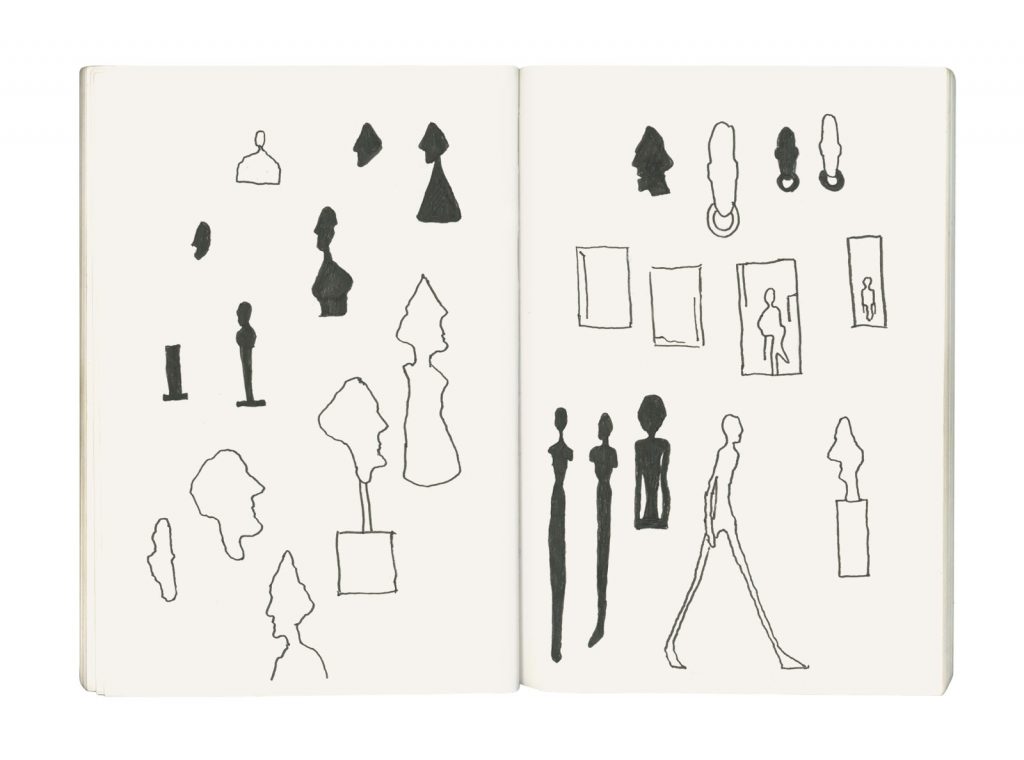

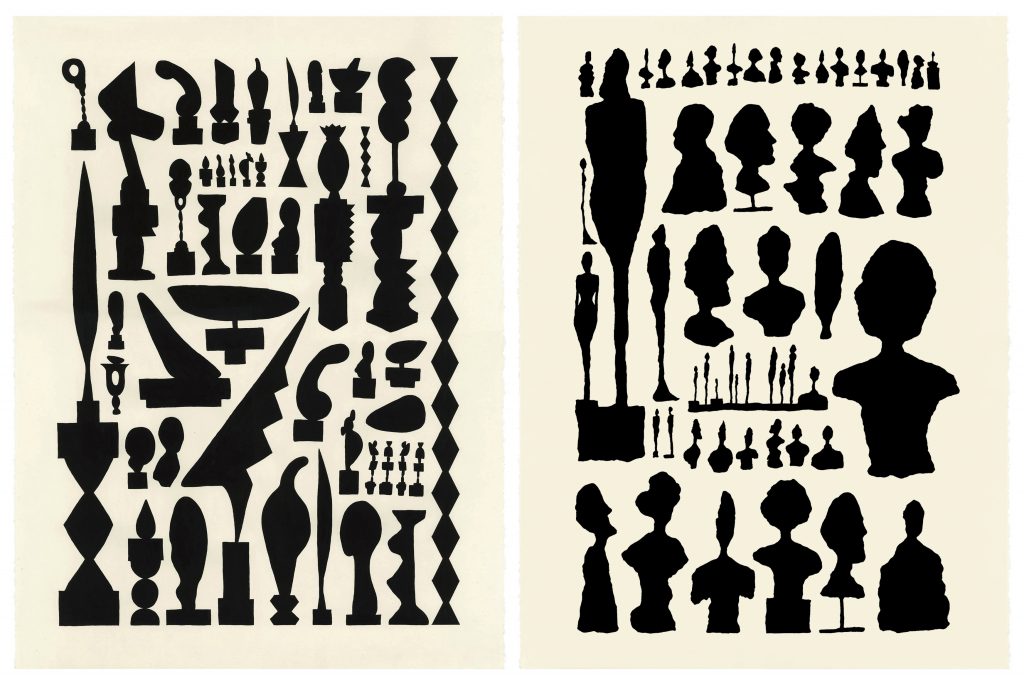

With this in mind, another body of work that caught our attention is her recent series of paintings and prints that explore the intersection of sculpture, typography, and semiotics. She exhibited a selection of this work in May 2019 at the 42 Social Club in Lyme, Connecticut, in a show entitled Glyptotek.

Images courtesy of the artist. ©Alexandra Zsigmond

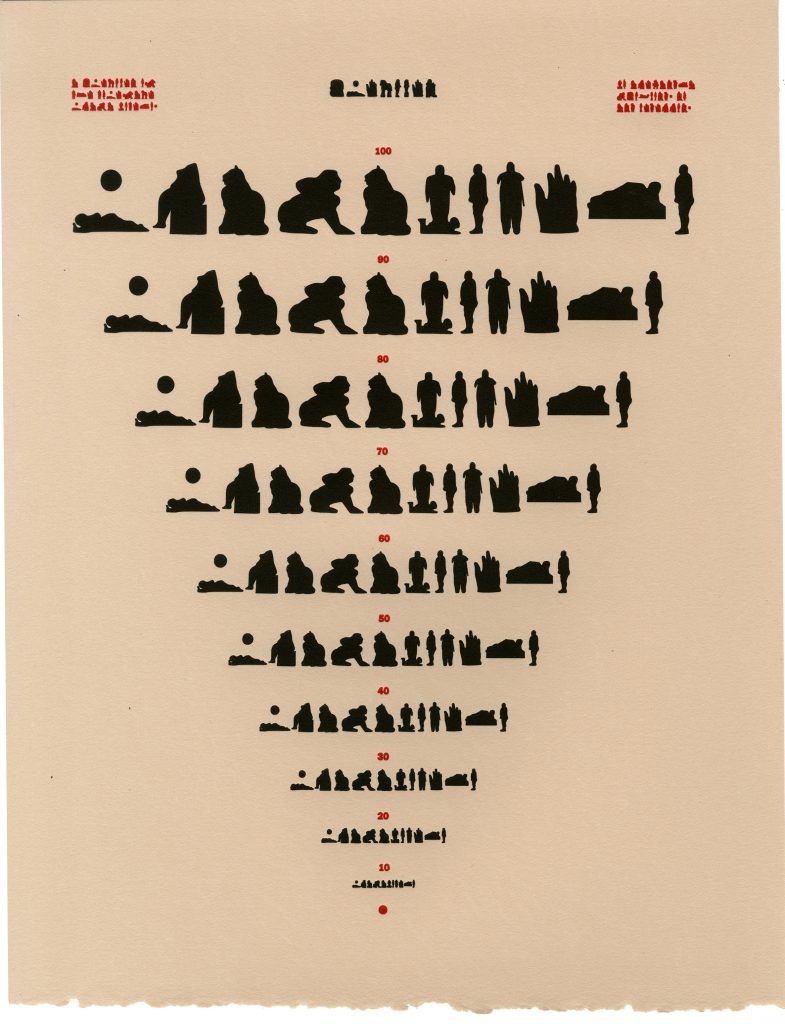

A glyptotek is a collection of sculptures; the word is derived from the Greek verb glýphō (to carve or sculpt) and the word thḗkē (a storage place). Glýphō is also the root of the word ‘glyph.’ In typography, a ‘glyph’ refers to a unique symbol, unit, or mark within a larger set; collectively, these symbols form a written language. And yet ‘glyph’ also means ‘a sculpted figure,’ an etymological connection that hearkens back to the origins of writing and printing. Ancient languages such as Egyptian hieroglyphics were carved into clay or stone, and the first printing presses relied on small letter sculptures that could be endlessly rearranged to form any text. And in modern Greek, the verb form of glyphō means ‘to follow and read a form with the eyes,’ emphasizing the age-old perception of sculpture as a form of language.

Images courtesy of the artist. ©Alexandra Zsigmond

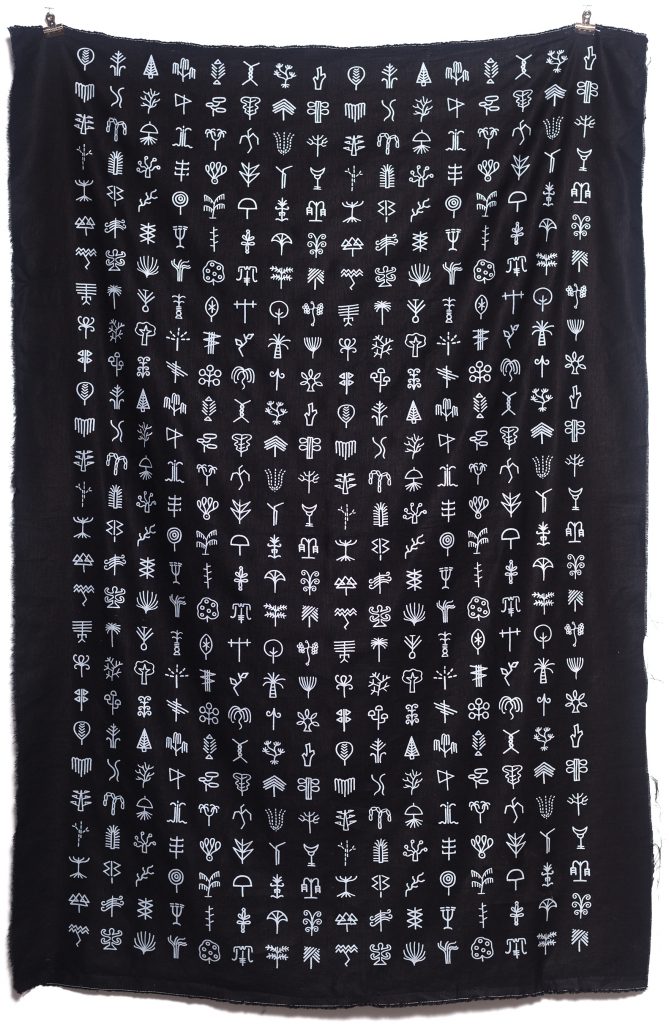

The paintings and prints in Glyptotek meditate on this obscured connection between sculpture and written language. They reimagine the three-dimensional work of three modern sculptors—Fernando Botero, Constantin Brâncuși, and Alberto Giacometti—as collections of two-dimensional glyphs. Each of these artists were inspired by ancient cultures, and Botero and Giacometti drew directly from Egyptian hieroglyphics in the creation of their work. This series illuminates those influences, rearranging the artists’ sculptures into a visual glyptotek of alphabets, charts, type specimens, and manuscripts. In doing so, it challenges us to consider the sculptor as scribe, carving written languages that follow visible yet enigmatic rules.

Alexandra’s paintings underline the continuity of sculptural and artistic vocabularies throughout history. Recently, she has also been working on a series of drawings on architectural metaphors in psychology, as well as a body of work entitled lexicon that evokes hieroglyphic languages from antiquity. Communication is an innate, age-old concern of the human race. While time has passed, and technologies have advanced, Alexandra’s practice reveals the ongoing necessity of language and form to communicate the most immaterial and conceptual aspects of the human condition.

This article was co-authored by the artist.