“Art is the highest form of hope.”

— Gerhard Richter

(quote from the 1982 text for the documenta 7 exhibition catalogue)

So many of us have been working from home for weeks now. Galleries, museums, cafes, and even some parks now have closed. Being an avid believer of seeing art in person, the quarantine we are experiencing collectively has rendered me restless, longing for that exciting inner turmoil evoked when in art’s presence.

There is extensive scholarship on the strength of art’s effect on an individual, from emotional to visual and beyond. Art has the power to ignite the mind and set it free to roam down paths known and unknown. The fact that we are confined indoors, and that art institutions and galleries have shut their doors due to safety concerns does not, however, mean we are solely reliant on the digital.

There is a number of artists who, in challenging notions of mediation, authorship and even authenticity, created works that could be recreated by following instructions. Others created textual works that, if read and enacted, would lead to an experience, and that very experience generated within you, the “viewer,” is the complete artistic product. This immediacy achieved by involving the viewer in the creative process is something that could even, possibly, be attempted at home.

Below I share a list of some beloved examples of such works that I thought could be fun to engage with, or in the least, offer some cultural food for thought. They certainly have the capacity to raise questions within you on traditional notions of authorship, cultural heritage, art as a conceptual and physical object, and of course what it truly means to experience a work of art.

One of the first artists to spring to mind when contemplating this topic of artwork that can be re-created was Sol LeWitt and his beautiful, geometric wall drawings. The wall drawings were a body of work that could be completed by, theoretically, anyone by following the artist’s strict instructions that outlined everything from the surface to the medium. One such drawing—Wall Drawing #370: Ten Geometric Figures (including right triangle, cross, X, diamond) to be exact—was installed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and opened on June 24, 2014. I was working there at the time, and watching it come to life in the first-floor hallway gallery was nothing short of magical. It was near impossible not to wonder what it would be like to have one created in one place or another.

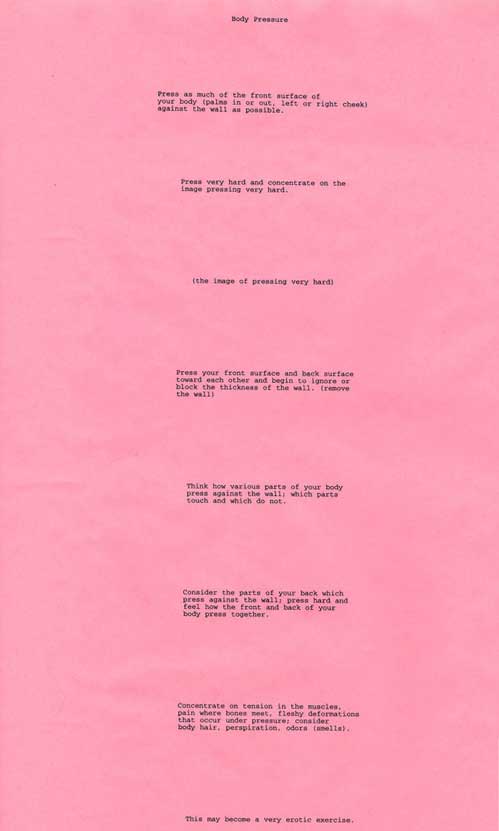

The next artist, Bruce Nauman…well, his work was staring me in the face, perched against my bedroom wall in its frame. Body Pressure, 1974 is a printed text outlining instructions on how to place your body against a wall, and where to place your attention while doing so.

It is an experience that engages the mind very deeply proving oddly meditative and, like the artist notes on the very bottom, a bit “erotic.”

Bruce Nauman, Body Pressure, 1974

Press as much of the front surface of

your body (palms in or out, left or right cheek)

against the wall as possible.

Press very hard and concentrate. From an image of yourself (suppose you had just stepped forward) on the opposite side of the wall pressing back against the wall very hard.

Press very hard and concentrate on the image pressing very hard (the image of pressing very hard) press your front surface and back surface toward each other and begin to ignore or block the thickness of the wall. (remove the wall)

Think how various parts of your body press against the wall; which parts touch and which do not.

Consider the parts of your back which press against the wall; press hard and feel how the front and back of your body press together.

Concentrate on the tension in the muscles, pain where bones meet, fleshy deformations that occur under pressure; consider body hair, perspiration, odors (smells).

This may be a very erotic exercise.

Of course, Laurence Weiner could not be found missing from such an article. The artist’s spray paint works in particular like ONE PINT GLOSS WHITE LACQUER POURED DIRECTLY UPON THE FLOOR AND ALLOWED TO DRY, 1968 and TWO MINUTES OF SPRAY PAINT DIRECTLY UPON THE FLOOR FROM A STANDARD AEROSOL SPRAY CAN, 1968 are such interesting examples as their very titles are the instructions for each one. I cannot recommend doing this in your home, though, at least not without proper ventilation. Nevertheless, these works demonstrate exactly that which Mel Bochner described in his 2009 article for October as artists “collapsing the space between the artwork and the viewer […] permitting the work to engage larger philosophical, social and political issues”[1]

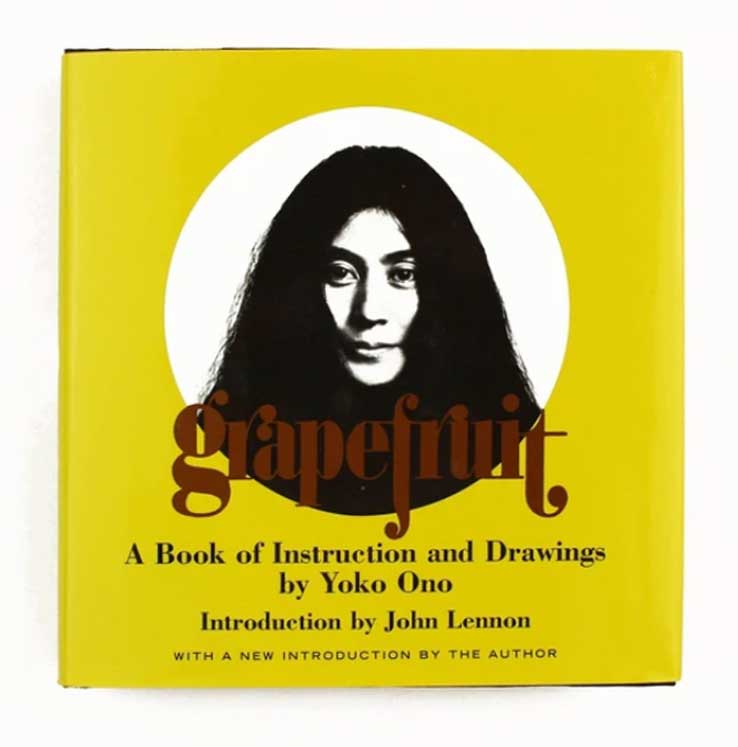

Something a little more evocative of thought, and probably less destructive of your living room floor are some textual works by Yoko Ono like this one below included in the book Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings:

AIR TALK (from Lisson Gallery brochure 1967)

It’s sad that the air is the only thing we share.

No matter how close we get to each other,

there is always air between us.

It’s also nice that we share the air,

No matter how far apart we are

the air links us.

Finally, this last example of work cannot really qualify as an “instructable” type of art but it is certainly something worth trying. When the mind is overactive, as it very much can be in such times of uncertainty, drawing can be a meditative practice.

William Anastasi created what are known as Walking Drawings and Pocket Drawings. The first Anastasi drew by placing a pencil or pen over a piece of paper, both held while he focused on the act of walking and taking in his surroundings. Similarly, pocket drawings were created by holding the tip of a pencil against a piece of paper that was folded small enough to fit in the artist’s pocket. The end results were drawings made mechanically and by chance that, nevertheless, mapped his body’s activity in a vivid and immediate way.

A diverse array of artwork that comes with instructions can be found in Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Do It: The Compendium. This book contains a plethora of artist instructions ranging from performance art to urban intervention, and philosophical reflection to recipes by artists including many of those mentioned in this article.

I hope this article provided you with some inspiration and joy. I hope it filled a little of that void created by missing your museum and gallery walks from the good ol’ days as I have missed mine.