Despina Konstantinides is a New York-based artist who has been working with oils and color nearly her entire life. She graduated from Trinity College with a degree in philosophy and received an MFA in painting from Indiana University. Drawing on her philosophical background, Konstantinides is interested in the underlying presence that holds a painting together. A primary element of her work is the investigation of form that is simultaneously abstract and representational. Her paintings oscillate in the existential sphere while also drawing influences from Byzantine portable icons and their ability to go past the representational, and depict the invisible mystical and sacred element.

Konstantinides’ work has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, and included in an impressive array of collections. Lately, she can also be found teaching undergraduate art history courses.

So needless to say, it has been a major honor to represent Despina Konstantinides on peri-Tēchnes, and to sit down with her for a (socially distanced) interview. Read below for our conversation.

Tiffany Apostolou: I am so excited to be interviewing you, thank you for taking the time to do this with me! Would you like to initially give us a small walkthrough of your path in art that led you to your current practice?

Despina Konstantinides: I’m thrilled to be here! Thanks so much for having me. As you might know, I’ve been painting since I was 8 years old. I learned the foundations of painting around then, and started my practice with realism. In college, however, I majored in philosophy and was really interested in Heidegger’s metaphysics and his concept of Dasein—the part within us that has access to the world beyond everydayness and that can encounter the “Being of beings.” While studying in college, I met Richards Ruben, whose definition of art synthesized my passion for metaphysics and my love of art. He said to me, “You—think to yourself. You, think to yourself all of the time. But who listens to you while you think? Who receives your thoughts? The listener [the receiver] within each thinker.” Art, [the late Richards Ruben suggested] gets to that part of the self, the receiver of thoughts.”

His concept of art bridged…connected my interest in metaphysics with my interest in painting. And it was my mentor, Barry Gealt, later, in grad school, who taught me the language of painting, meaning, how to see past the image and into the painting. With those tools, I slowly began to shift away from painting-from-reality to painting from within.

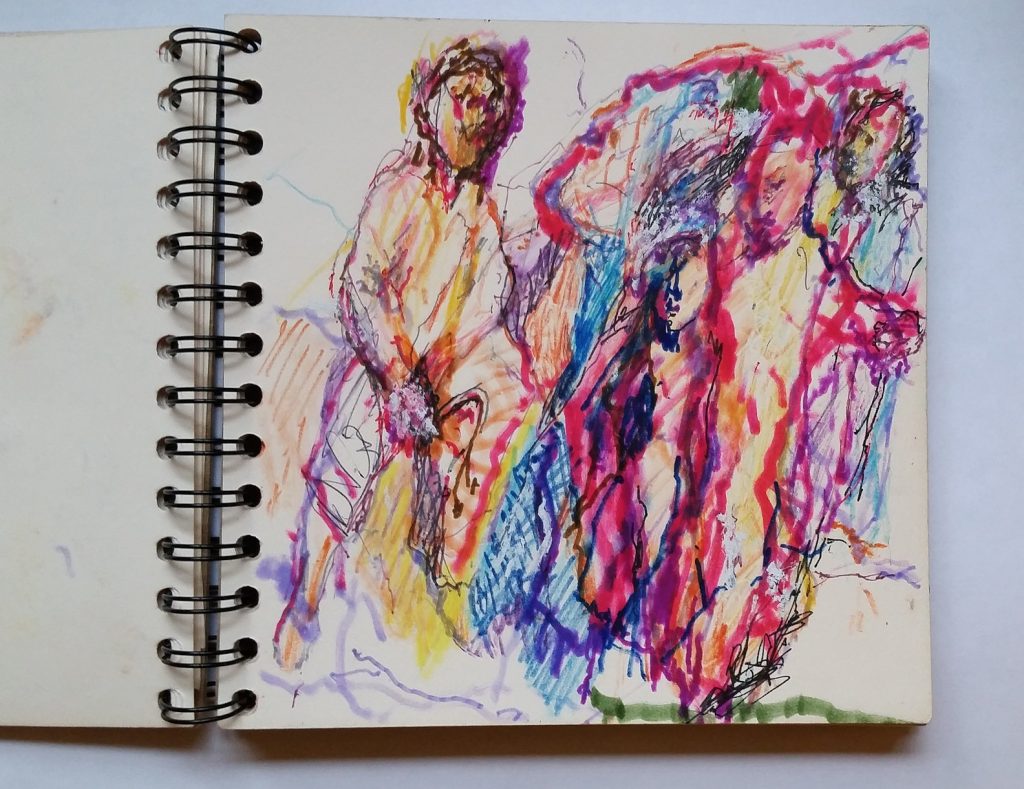

© Despina Konstantinides

TA:I think the very first, instinctual thing that drew me to your work was your layered and textural use of color. It keeps the eyes moving across the entire work and creates this insatiable desire to merge with it. Would you like to talk a little about your technique?

DK:For me, in many ways, painting is about finding form. My painting process involves adding and eliminating layers of paint-color in search of form. And by form, I mean, finding my handwriting, my voice in each painting. If you look at a Monet, Vuillard, Gealt, or David Lund, you know who the artist is. That’s what I mean by form.

TA: I see, that makes total sense.

Your large scale works, the ones I got to be introduced to first, also present this incredible quality of layered color, and form as you describe it. When looking at them you feel a timelessness and weightlessness—almost like levitation. I feel like this is an effect of how you depict space, free from strict traditional methods of perspective or aerial. Am I close?

DK: “Levitation,” that’s a good word. I’m interested in paintings that hover in the space between knowing, and not knowing your existence. For me, the creative process itself involves getting yourself into that experience of knowing what it means to be human and, simultaneously, having no idea what it means to be human. I think that any timelessness or weightlessness in the work has to do with that kind of creative experience.

Photo courtesy of the artist. © Despina Konstantinides

TA:This sensorial effect reminds me of Byzantine iconography where the space behind the figures defies natural laws, the perspective is broken, and the space built, natural or even neutral is infinite and timeless. Is this an influence you have considered in your work?

DK:For the Byzantines, the icons weren’t just images, they were gateways to a divine dimension. I’m interested in this concept of painting as portal. The manipulation of all the elements in a painting, space, composition, paint handling, form, all has to do with the notion of doing whatever it takes to access something unknown, fleeting and internal. With painting, what I’m doing is chasing the unseen.

TA: On the note of Byzantine influences, the sense of timelessness is also achieved through the use of light, and golden reflective surfaces. How does your work connect to that?

DK: When I am fully present in the act of painting and suspend judgment, something indescribable happens to time. It’s like you blink, and it’s two hours later. That’s what if feels like. I play with time this way. The experience of time, while in the mode of creativity, is different. The more connected you feel to everything around you, the faster time flies. If you have that experience while painting, I believe that it will come through in the work and transform the very quality of the paint itself. Viewers will experience that sense of timelessness without necessarily being able to put their finger on what exactly they are responding to. I can’t describe it. I think that it has to do with what happens to time when you are fully present. It’s this quality that Philip Guston talks about when he talks about the mystical element of the picture-plane. If you give it all you got, the very molecules of the paint themselves, transform.

TA: I think you described it perfectly. It is this experience of communion and immersion with the picture-plane!

Recently, you began showing smaller works, you call them seedlings. (We feel so lucky to have some featured in your artist page on our website.) Were they originally, studies for your larger paintings?

DK: I work on my large paintings for months, sometimes, years—there was a strong desire to do something quicker alongside the larger works. I think of the seedlings as an introduction to my larger paintings. They are meant to ignite a spark.

© Despina Konstantinides

TA:I do love how they have taken a life of their own, yet, they still retain such strong intellectual consistency with your larger paintings. The smaller scale, alongside the earlier references we discussed, brings to mind portable icons. Especially when considering they are painted on wood panel. Was this intentional?

DK:Yes! I like that! Portable, portals. But it wasn’t intentional, it’s a happy accident. I like to think of the seedlings as offerings. They spark, or offer, a reminder of a portal unveiling what is within you. The icons grounded the believers, they were a kind of compass that they carried along with them and passed along to loved ones. I love that notion of artwork as a grounding presence that reminds, unveils, and ignites the question “what are you in it for?”

TA: You put that beautifully…

Art—creating it but also viewing it—can be such a spiritual experience. I’d love to talk a little more about that with you.

DK: Great point. I think that the kind of creativity that I’m interested in involves an existential experience. And by existential, I mean, questioning your origin, your possibility of non-existence. There’s an element to hovering between this world and nothingness that I look for in painting. It is interesting to me when I feel that the painting exists within a space where more difficult, existential questions, can be accommodated. The space itself can handle the weight of certain questions. If the artist has that experience during the act of creativity, the painting will be a record, a witness of that experience and it will come across in the work viscerally and affect the viewer. It gives off this quality of the painting knowing you better than you know yourself. And you walk away feeling understood…reconciled.

TA: As an artist with Greek heritage, do you feel that your work is in some way informed by it, other than the Byzantine references?

DK: If you go to the New Acropolis Museum, on the top floor—that looks out to the actual Parthenon— you’ll see these stunning marble reliefs that are presented in such a way that you can see the back of them. Have you seen these? What are they called?

TA: Oh yes! That is actually my favorite floor. They exhibit the ζωφόρος, the frieze, perimetrically. For anyone who might not know, this is the sculptural element that sat above the columns and directly below the roof line. Per the museum’s architects the installation of the frieze was intended to create a stronger effect in the viewer as they look upon the building outside while walking around the very part they would not be able to fully see from ground level on-site. Not to mention the color-difference between the few remaining parts in Greece and the replicas still housed at the British Museum, but I digress!

DK:Yes, thank you! The museum must consciously display the frieze so that you can see the back of each block. In some ways, the backs of these reliefs are fully realized paintings. They float between figuration and abstraction and enter a realm I can’t describe in words. There’s something so life-affirming about these things, so colorful, so formed.

But back to your question, the cultural idea I owe to my Greek heritage, and the gift my parents have passed along to me, is this concept, and more precisely, this embodiment of “orexi.” Orexi means a yearning, longing, appetite, and striving for life. When you’re painting, you’ve got that same compass, a longing for, fighting for life. I’m not making pretty pictures or mixing colors, in essence I am fighting to unveil deeper parts of myself—I’m fighting to access inaccessible parts of me. And I am also fighting to hover in that creative space. It’s completely unnatural, you know, to stay in that creative space. I always resonate with documentaries of athletes, pushing their bodies to extreme. Have you seen The Barkley Marathons?

TA: No, but I have heard of it and am definitely adding this to my list—you give the best recommendations!

DK: It’s this absolutely ridiculous documentary about a race this guy created that literally involves running 100 miles within 60 hours. That’s over three back-to-back marathons. It’s completely insane! And yet it still hits a nerve insofar as it has to do with that notion of pushing yourself to the limit, and seeing what happens next. In a sense, as a painter, you’re doing the same thing. You have to be tireless, relentless, bull-headed. You’re fighting to access something inaccessible.

TA: Who or what have been some of the most influential figures who helped you in your artistic path and reaching your own unique expression?

DK:Heroes from the past that got into my DNA: Morandi, for his sense of touch and sincerity in everything he put down in paint. Seeing Hercules Seghers, the 16th century Dutch artist, was like a sharp wake-up blow in the gut. How does he float in that world between being and non-being? How does he know me better than I know myself?!

Piero has a stillness to his paintings that comes from oscillating so fast. The Arezzo frescoes in Tuscany, were like nothing I had seen before. These paintings have nothing to do with being calm or quite. Instead, they are still: a wavelength vibrating at the highest frequency appears still. The stillness comes out of high motion, high engagement, incredible presence. This is a quality that I look for, that makes me want to take works home with me.

TA: How about some works and people who currently influence and inspire you?

DK: Current sources of inspiration…

When I saw my first Mark Bradford, Backward C, at the MFA in Boston, it stopped me in my tracks. A large mixed media collage, that had a quality of oscillating between being and non-being. John Lees, who shows at Betty Cuningham Gallery, has that same quality and a real honesty to his work.

Adrian Ghenie, the Romanian painter, I think is something to be reckoned with as is Amy Sillman.

I am also extremely lucky to have found a mentor in the painter, David Lund who lives and works in New York. He is 95 years old and making his best work now. They’re these small works on paper, about 7 x 7 inches, that tap into something inaccessible and have, by the way, completely taken over his life. And by taken over his life I mean, he’s up till 4 in the morning, working. It’s not just not a night-time thing, it’s daytime too. I’ll talk to him and he’ll say that it was all of a sudden, 3pm and he realized that he had forgotten to eat something since his morning cappuccino.

Photo courtesy of the artist. © David Lund

TA: I love it when such influential artists switch to a smaller scale. It gives such an incredibly intimate view of their work and its evolution.

DK: He has just tapped into something indescribable, invisible, transcendental. He has become this vessel for the work. And speaking with him is simply electrifying. Quite frankly, it’s contagious… I mean, he forgets to eat, for God’s sake! Let’s take a second here to recap and put this in perspective: He’s 95 years young, been “quarantine-ing” in isolation for some good 8 months now, and I can’t even get the guy to call me back half the time. When I think, what am I in it for—it’s that.

TA: He is truly, a remarkable man, in every sense of the word. And such a Rennaisance man too! Not to even touch on the mastery of color, which, I hope you will allow me to say…I really see in your work too.

DK: There is so much to process from these works – the relationship between space and color alone…I am just beginning.

TA: Thank you again, Despina, so much for chatting with me! It has been absolutely wonderful!

Notes & Links:

See available work by Despina here

Despina Konstantinides’ website

David Lund

Amy Sillman

Richard Rubens

Barry Gealt

Aside from the Icon provided above, see also: the Menologion of Basil II, illuminated manuscript, compiled c. 1000 AD, for the Byzantine Emperor Basil II. Vatican Library, Italy.

New Acropolis Museum

The Barkley Marathons, movie